.jpg.cdd7f8371d17e2f2f2e2a0e21e02f727.jpg)

Canny lass

Supporting Members-

Posts

3,629 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

426

Content Type

Forums

Gallery

Events

Shop

News

Audio Archive

Timeline

Everything posted by Canny lass

-

I think it might be the other way round, Jammy. Howard Terrace came first. Reedy's dad described the area in the 1950s -60s and said "Starting at what used to be Joe Jennings farm and shop including Mansion House now possibly 'Smiles' was Glassey Terrace. The first 7 houses were originally named Howard Terrace but the name was changed to Glassey Terrace as a result of misdirected mail as another Howard Terrace existed in Netherton". Howard Terrace must therefore have started at Mansion House and could only be extended towards the Bank Top. Looking at the present day Glassey Terrace it's possible to see where the extension started because of the differing roof- and upstairs window heights: I'm pretty certain I've seen Howard Terrace in an early census. I'll see if I can find it. There was a Howard terrace at Netherton Colliery. It was renamed Office Row but I don't know when.

-

These are two different Puddlers Row. The 'old' Puddlers Row is also shown on the 1859 map but unlike the 'new' Puddlers it is on the east side of the main road. The old Puddlers Row belonged not to Bedlington Station/Sleekburn, but to 'Village of Bank Top', according to census information, and was there before Glassey's arrival in 1867. It appears in the 1871 census as a row of 22 dwellings. Glassey left Bedlington in 1884 and the old Puddlers Row still appears on OS maps in 1898 but without a name. On the same map the new Puddlers Row appears running east-west along what later became Stead Lane. We can also see here that the west side of the road, north of the Bank Top Hotel, is still not developed. At some point between 1897 and 1922 we can see a devlopment on the west side of the road - the area now occupied by Glassey Terrace. This is called Front Row. New development on the east side of the road in the area of the old Puddlers Row, includes a 'Back Row' and what could be old Puddlers Row but with an extension. By 1947 Puddlers Row is no longer shown on the OS maps and Front Row is still called Front Row - not Glassey Terrace.

-

.thumb.jpg.7493ddab4a696108cf2b849323d3c155.jpg)

Bedlington Station - Miners Houses Ownership

Canny lass replied to tullybrone's topic in History Hollow

Is it perhaps time for a new set of specs? Bedlington A Pit is shown on the map above. Directly above the 'O' in BEDLINGTON. -

-

-

I thought that i'd finished my research on Puddlers Row way back in August 2017 (earlier in this topic). However, because of Evans' statement I've had another look. If Glassey bought Puddlers Row and renamed it Glassey Terrace, then it was not the Glassey terrace which we know today. Glassey terrace doesn't appear on OS maps until the period between 1897 - 1922 and by then Glassey had left Bedlington having emigrated down under in 1884. Glassey must have bought the old Puddlers Row which fronted the main road exactly opposite the present Glassey Terrace - the site now occupied by Melrose Avenue. The present Glassey Terrace may well have taken over the name but was originally built as Front Row, as far as I can deduce from the OS series of maps.

-

Day 183 of isolation for me today. The house has been cleaned from top to bottom and the garden has had the overhaul of a lifetime! Every tree has been pruned, some in late spring some this month. Knowing we'd be at home through the summer we over-fertilised the lawns in an attempt to kill the moss, which has made a strong take-over bid these last few years. It's been a great success, though it has resulted in an increased need for grass cutting, 2½ hours every other day since May! This job has fallen to yours truly as the OH's skills were needed elsewhere (repairing a collapsing balcony and re-laying the patio under it). Together we have also widened the driveway by 50 cm by digging out the lawns which had grown into it over the years. We've resurfaced with 30 tons of natural gravel - all raked out by hand. Being at home we've been more in touch with what's going on around us. We've always fed birds and squirrels (which have their very own resaraunt here) but this year I've reared a family of five who seem to have lost their mother. They've all flown the nest now but I've adopted a hedgehog instead, who moved into my OH's workshop among all the oily rags , old paint tins, dried up paint brushes and a miriad of other "things that might come in handy one day". Then there's been mushroom and berry picking. I do this every year but I this summer have excelled myself: 27 litres of chantrelles, 16 litres of ceps, 8 litres of wild raspberries, 16 litres of blueberries and 11 litres of "lingon". I had to look this up and it seems they are called "cowberries" in English. I've never heard this before but, on the other hand, I've never seen them in England either. The freezer's full and so is the jam shelf in the pantry. We've only left the house three times for essential errands: collecting a passport from the police (the issuing authority), vaccination against TBE and a hospital visit for my OH: We get out and about to the surrounding forests and lakes for walking and swimming and use the telephone and Skype for family contact - we've become great grandparents for the first time so it's been used an awful lot as we are unable to visit. Things seem to be going well, generally speaking, for the country as a whole and we pensioners are to recieve a pension increase and a tax reduction next year, by way of thanks for staying at home! I need a holiday!!!! How's the situation in Bedlington today? Heard on the news today that the North East is being locked down. Must be bad when we are hearing about it here. .

-

There have been a lot of suggestions as to the whereabouts of Puddlers Row at Bedlington Station. Just to add to the confusion, Evan Martin in his book Bedlingtonshire Remembered says the following (page 57) in relation to the Barrington and Choppington brickworks: "Local worthies Dr James Trotter and Thomas Glassey, encouraged miners to take shares in brick companies. Glassey himself bought Puddlers. Row at Bank Top and renamed it Glassey Terrace before emigrating to Queensland". PS Thanks for the tip-off, Eggy. A thoroughly good read!

-

Here it is! A bit late but we've had real summer weather today so I finished off the gardening chores before it gets dark. 1. Nairobi is the capital of which African country? 2. Which planet is nearest the sun? 3. What name, derived from the Latin for ‘old man’, is sometimes given to the legislative assembly of a country? 4. Which wine is flavoured with pine resin? 5. Which organ is inflamed when you are suffering from Nephritis? 6. Which swimmer won seven gold medals at the 1972 Olympic Games? 7. Who was the last prisoner to be held at the Tower of London? 8. Which bottle size is equivalent to 12 standard bottles? 9. Which West End and Broadway musical was adapted from T.S. Elliott’s Old Possum Poems? 10. How many points win a game of Cribbage? 11. What name is given to an eagle’s home? 12. What do we call the chemical process by which a substance combines with oxygen to produce heat and light? I’ll bet you didn’t know …. William Wordsworth was, at one time, thought to be a French spy and was followed for a whole month by a detective. Answers on Thursday.

-

.thumb.jpg.7493ddab4a696108cf2b849323d3c155.jpg)

Does Anyone Know Anything About The Glove Factory ?

Canny lass replied to katie's topic in History Hollow

Naturally, I should have said on the LEFT. I haven't known my ass from my elbow for many years but not knowing right from left is unforgivable! -

Answers to last week's quiz: 1. No ball 2. Oscar Wilde 3. A pine cone 4. Knitting 5. Amplitude modulation 6. Goat island 7. Who Framed Roger Rabbit 8. Gail Devers 9. Airedale terrier 10. You forgot 11. Five 12. Vitamin D I thought I'd made it really difficult this week. Clearly I underestimated the amount of trivia you people already know. I must try harder tomorrow!

-

.thumb.jpg.7493ddab4a696108cf2b849323d3c155.jpg)

Does Anyone Know Anything About The Glove Factory ?

Canny lass replied to katie's topic in History Hollow

Last photo, from Claire Gates: That's Dorothy (Dot) Lumsden (with glasses) on the far right. -

-

This week's quiz: 1. What does a cricket umpire signal by raising one arm horizontally? 2. Which writer was imprisoned because of his relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas? 3. A strobilus is another name for what? 4. What was the occupation during the French revolution of a tricoteuse? 5. When referring to radio waves what do the initials AM stand for? 6. Which island separates the two principal parts of Niagara Falls? 7. In which film did Bob Hoskins play Eddie Valiant? 8. Who won the women’s Olympic 100 metres in 1992? 9. Which terrier is the largest of the terrier breeds? 10. In mythology what happened if you drank the water of the River Lethe? 11. For every seven white keys on a piano how many black keys are there? 12. The deficiency of which vitamin can cause rickets? I’ll bet you didn’t know …. Queen Christina of Sweden had a 10 cm long cannon which she used to fire cannonballs at flies! Answers on Thursday.

-

-

Answers to last wek's quiz: 1. Roderic (Rod) Evans 2. Judy Garland 3. Brighton and Hove Albion 4. Social Democratic Party (SDP) 5. Marsupial 6. Tegucigalpa 7. The Potteries 8. Barnes Wallis 9. 1.5 miles 10. Lloyd George 11. Barium 12. Full of woe You lot are getting too good at this! Going to make them more difficult!

-

This week's quiz: 1. Who was the original lead singer with heavy rock band Deep Purple? 2. Who was Liza Minelli’s famous mother? 3. Which football league club used to play at Goldstone Ground? 4. Roy Jenkins was the founder of which political party? 5. What type of creature is a ‘flying phalanger’? 6. What is the capital of Honduras? 7. What name is commonly given to the area around Stoke-on-Trent? 8. Who invented the bouncing bomb (and no, it wasn’t Bobby Ball)? 9. Over what distance is the Classic horse race ‘The Oaks’ run? 10. Who coined the phrase “a land fit for heroes to live in”? 11. Which reactive metal is represented by the symbol Ba? 12. If Monday’s child is fair of face what is Wednesday’s child? I’ll bet you didn’t know …. Queen Elizabeth I was the first English queen to see herself in a mirror. She banned them from court as she aged. Answers on Thursday

-

.thumb.jpg.7493ddab4a696108cf2b849323d3c155.jpg)

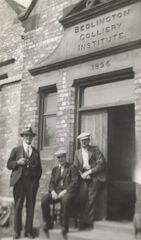

A Pit Institute c1950s.jpg

Canny lass commented on Alan Edgar (Eggy1948)'s gallery image in Historic Bedlington

-

.thumb.jpg.7493ddab4a696108cf2b849323d3c155.jpg)

A Pit Institute c1950s.jpg

Canny lass commented on Alan Edgar (Eggy1948)'s gallery image in Historic Bedlington

Last part of the institute building, to the far right, must be what's noted as "policeman's dwelling" on the drawing. Would I be right in thinking that this policeman was the 'collry poliss' rather than a member of the constabulary. I know that the colliery policeman at Netherton (Geordie Collis) was employed by the Howard Pit and he had a colliery house but he wasn't a 'real' policeman. We used to sing a song about him: I wish I was a poliss, a big fat poliss Wi feet like Geordie Collis, the big fat poliss. Kids can be cruel!

.thumb.png.5266994e12c8c678a494599b1a1e7840.png)